Tove Kjellmark Swedish, b. 1977

Further images

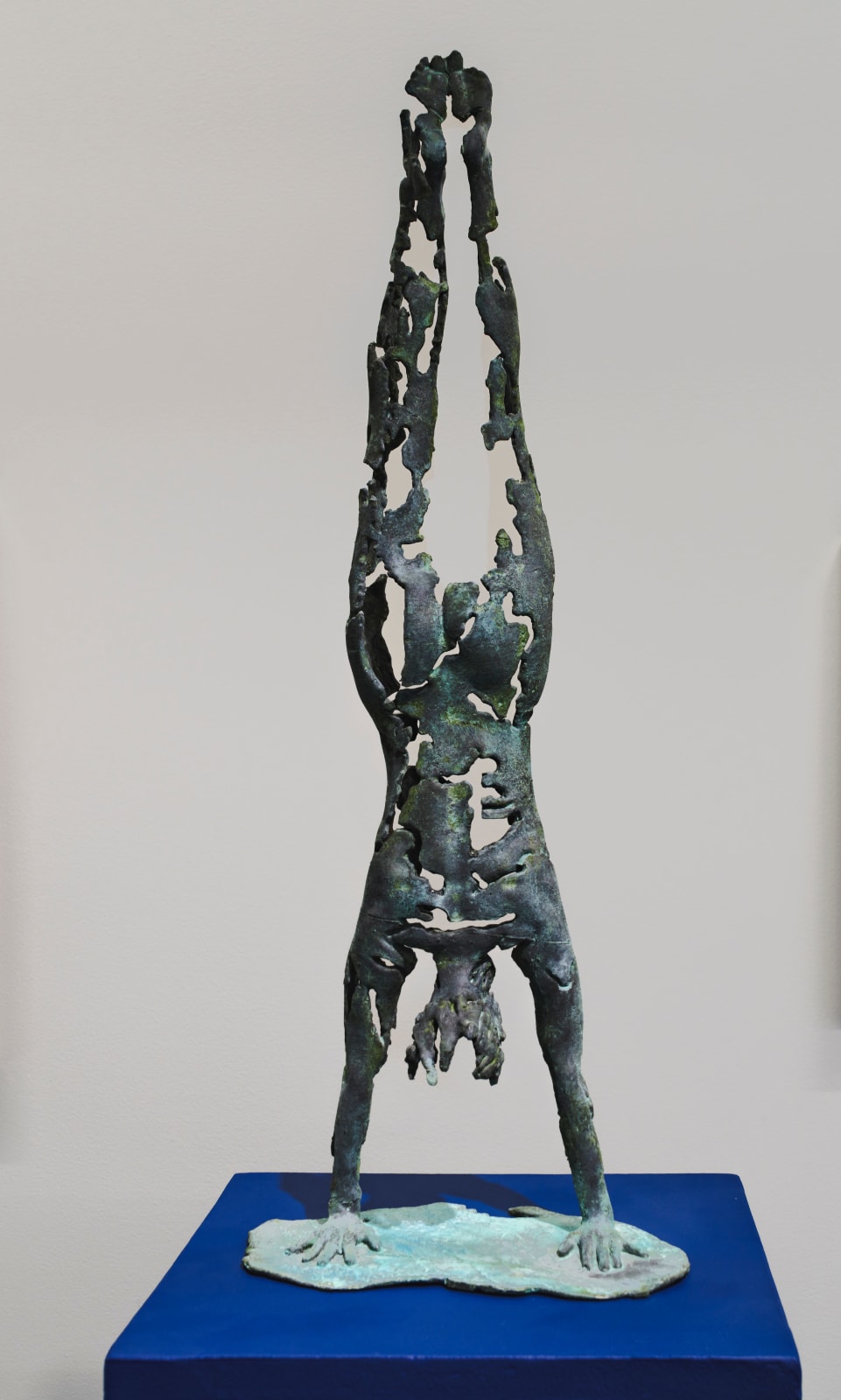

The idea of this sculpture comes from my private experience of dealing with life-changing crises, schizoaffective disorder, and how I felt after two years of intense therapy. They said I was ready, but I felt like I was broken into pieces. I didn’t know how to put the pieces together again. I practiced a lot of yoga, it was my best “medication”, and during my practice, I got the clear insight that it is in the cracks light comes out. That I needed to break to expand, that there are movements in both directions.

The bronze sculpture “When I Crack I Expand” can be read as a paradox; expansion [involves fragmentation] and [is] unifying at the same time. Sometimes, when you feel that you are falling apart, you may actually fall into place.

I have experienced unpredictable hallucinations where my body dissolves and spreads into space. I sit in the car and suddenly shapes and spaciousness merge, it is almost as if you feel that you are one with everything and every atom individually. It has been both inspiring and at the same time frightening. But I’ve learned how to deal with it now and I can see a strong connection between those experiences and my attraction to the fragmented aesthetics, dissolved physicality, and transformations that I have worked with now. Working with 3D, where there is no scale and the relationship between inside/outside, and body/space is blurred, reminds me of the experience of my first psychosis. If you are inside a 3D model of a scanned body, it can just as easily be perceived as the universe, for example.

The significance of the handstand. Tove Kjellmark in conversation with Sonja Smith-Novak.

Initially trained as a sculptor, Tove Kjellmark has developed a multi-faceted experimental practice where she moves freely between multiple media and materials. Through sculpture, performance, drawing, and video, she examines sensations of embodiment and reflects on the dissolution of bodily boundaries in relation to surrounding nature. One of her works is a sculpture in bronze, with a stained color-painted plinth in wood. It shows a cracked person doing a handstand and is absolutely stunning to look at. We got together with Tove to find out more about this creation, “When I Crack I Expand”.

HSPM: It appears that this sculpture evolved from a first approach in your exhibition “The Human Assemblage”. This suggests that “When I Crack I Expand” took shape as the global pandemic and other crises roiled the world. Could you take us through the story of how the final sculpture came to life? How (if at all) was it influenced by what was going on?

The idea of this sculpture comes from my private experience of dealing with life-changing crises, schizoaffective disorder, and how I felt after two years of intense therapy. They said I was ready, but I felt like I was broken into pieces. I didn’t know how to put the pieces together again. I practiced a lot of yoga, it was my best “medication”, and during my practice, I got the clear insight that it is in the cracks light comes out. That I needed to break to expand, that there are movements in both directions.

The bronze sculpture “When I Crack I Expand” can be read as a paradox; expansion [involves fragmentation] and [is] unifying at the same time. Sometimes, when you feel that you are falling apart, you may actually fall into place.

I have experienced unpredictable hallucinations where my body dissolves and spreads into space. I sit in the car and suddenly shapes and spaciousness merge, it is almost as if you feel that you are one with everything and every atom individually. It has been both inspiring and at the same time frightening. But I’ve learned how to deal with it now and I can see a strong connection between those experiences and my attraction to the fragmented aesthetics, dissolved physicality, and transformations that I have worked with now. Working with 3D, where there is no scale and the relationship between inside/outside, and body/space is blurred, reminds me of the experience of my first psychosis. If you are inside a 3D model of a scanned body, it can just as easily be perceived as the universe, for example.

So another layer of this work is about the shifting relations and perceptions of life in the light of new knowledge.

Yes, I believe that some people, especially sensitive artists, can pick up indications of what is going on in the world very early. I can only speak for myself, but I started ‘prepping’ one year before the global pandemic (for the first time in my life), and my family was laughing and making fun of me! Then you know what happened at the beginning of the pandemic, the stores became almost empty!

During moments of cataclysmic change, the previously unthinkable suddenly becomes reality. And that can be for the good! While working on this sculpture, I thought a lot about human fear of change, and how it sets hooks for our development. It became very obvious during the coronavirus pandemic. But what gave me hope was to see how those in power are able to act when faced with an emergency. It shows that in a crisis, you act, and you act with necessary force. The climate crisis needs to be treated with the same urgency.

This sculpture signifies to me that you need to challenge yourself to be able to grow. This is highly relevant in the face of climate change, which is forcing us to look at ourselves from a more holistic perspective–and thus emerges the question of responsibility for the common body. Ecstasy, transformation, friction, orgasm, energy, breakdown: the curious mechanisms for some kind of change to happen.

HSPM: Can you go deeper into the creation process of your sculpture? How did it relate to your previous exhibition

The Human Assemblage?

The Human Assemblage was a show [based on] the idea to move my “in-progress” works from my messy studio into the white cube. The sculpture “When I Crack I Expand” was part of that exhibition but in plastic.

I am conscious of the world by means of my body. I live my art. Each subject that I portray, I first occupy with my own body, before it transforms into a sculpture, a drawing, or a video installation. In this case, I used a 3D scanner as a first approach. I asked a friend to scan me when I was hand-standing. The scanner attempts to stitch together fragments of reality, to correlate with how I experience life, dreams, and memory, and how my brain works, I guess. Everything is entangled and in motion. I remodeled and worked on the shape for quite a while. I aimed to take away as much as possible, be able to see through the body, unite it with the landscape but keep the shape of the body. Then I 3D printed [everything] piece by piece, and stitched them together like a modern-day Dr. Frankenstein. The sculpture then needed to be transmitted into a heavier material with historical connotations. Bronze. I wanted to keep the calligraphy, or the handwriting, of the machine in the work. I also wanted my fingerprints on the work.

Throughout my artistic career, I have explored the paradoxical mechanisms of development and change in different ways. Uncertainty often plays a major role in such processes. You need to let go of control and welcome mistakes and errors. Be present when unpredictable things appear. Which I love to observe in my studio. For me, artistic values have to do with instability, unlearning, and transformation. I find it much more interesting to study the transformations that take place in the creative process than the final result. To observe how a form comes alive when I transform it from a 3D-printed plastic to bronze. It is not possible to describe in words, it must be shown live because words are movements that have solidified. So in this exhibition, I wanted to share the conformation, the process, instead of a few end results.

HSPM: Why did you choose bronze?

Bronze is a very soft metal to work with. Together with polymers, it is one of the few materials that lasts as long as we will have an Earth left. I think of how Earth would look when humans are not there anymore. It can be a bit cliché to use as traditional a material as bronze, but to cast a bronze sculpture from a 3D model is an interesting new way of working. It places itself in liminal spaces between the digital and the organic, the past and the future.

HSPM: It’s very interesting how you make that connection between the digital and the organic throughout your artwork. When you say you think of what Earth would look like when humans are not there anymore, is there a way you imagine the extinction of the human race? And how does your art play into that?

In my work, I search for Another Nature. A nature that refuses to accept a difference between technological and natural forces, between human life and animal life, and between mechanics and organics. By researching precisely these issues, I want to challenge nature, creating it anew. Not out of critique, but because this kind of artistic experimentation is the only way another world is revealed.

I think it is important to talk about what Earth would look like without us! Are we survivors or fossils in the journey of tomorrow?

According to research, biological nature would take over and destroy most of what we humans have built. And pretty fast! For example, most houses will disappear in 100 years. [Yet] all sculptures made in Bronze will remain for thousands of years.

HSPM: What does the handstand signify for you?

Handstands help me to bring a new perspective to life, to boost the body’s energy, and build confidence in the mind. For me, they are one of the most challenging balancing poses that make me engage my physical and mental body.

Changing my environment or my point of view is necessary for me to get a new perspective on things. When I stand on my hands, I turn my body upside down, the feeling of the body’s relationship to space is strengthened, I really feel the space, and new nerve pathways are created.

Since I was a child I have always found it amusing to turn myself upside down. Handstands, headstands, and aerial acrobatics have been a natural part of my life. I am an amateur, I’ve never been into any serious sports, but when I get tired in the afternoon working in my studio, or when I am bored, I play around with handstands.

The handstand as an act contains so many symbolic pieces of the puzzle. To be able to stand on our hands, we need to activate all parts of the body. Everything from fingers to core, to toes. It also requires courage and body awareness.